9 Things You Should Know If Your Child Is Using Heroin

by Jeremy Galloway

The recent spike in the use of heroin and other opioids, sparking frightening headlines about addiction and overdose, has left families struggling to find solutions. When my family discovered I was using heroin over a decade ago, when I was in my mid-20s, they spent years trying to help, but didn’t know where to begin. Together, we learned the hard way that many potential “fixes” end up being dead ends. Some might cause even more harm.

There are so many things which, had we known them then, might have spared us years of pain and strained relationships. This isn’t a comprehensive guide, but these tips should be a helpful starting point for family members looking for answers.

1. Who’s to Blame? Well, It’s Just Not That Simple…

Experimenting with substances is normal. People have been using psychoactivesubstances for thousands of years and only a fraction of us become addicted. Contrary to the “gateway theory,” only 4 percent of Americans who try marijuana go on to experiment with heroin (1). The UN and leading experts—including Influence columnists Stanton Peele and Carl Hart—agree that most drug use, regardless of the type of drug, does not turn out to be significantly problematic.

Of course, that’s little consolation to the parents of people who do become addicted or otherwise place themselves at risk. It’s common for parents to either blame themselves or divert blame onto someone else, such as the “wrong crowd”, or a romantic partner. Given the pain and fear you may be experiencing, it’s natural enough to feel like you need someone to blame.

But there are parts of our lives you never see. Things we can’t share. Abusive situations where you struggled to keep us safe, alive, off the streets. Trauma, stress, or mental health issues that even we won’t understand until years later.

Pointing fingers is a distraction: People continue using substances, despite harmful consequences, for reasons.

Our first objective should be reducing any harms related to substance use. Only then can we help loved ones who want to seek additional help or to change their lives in other ways.

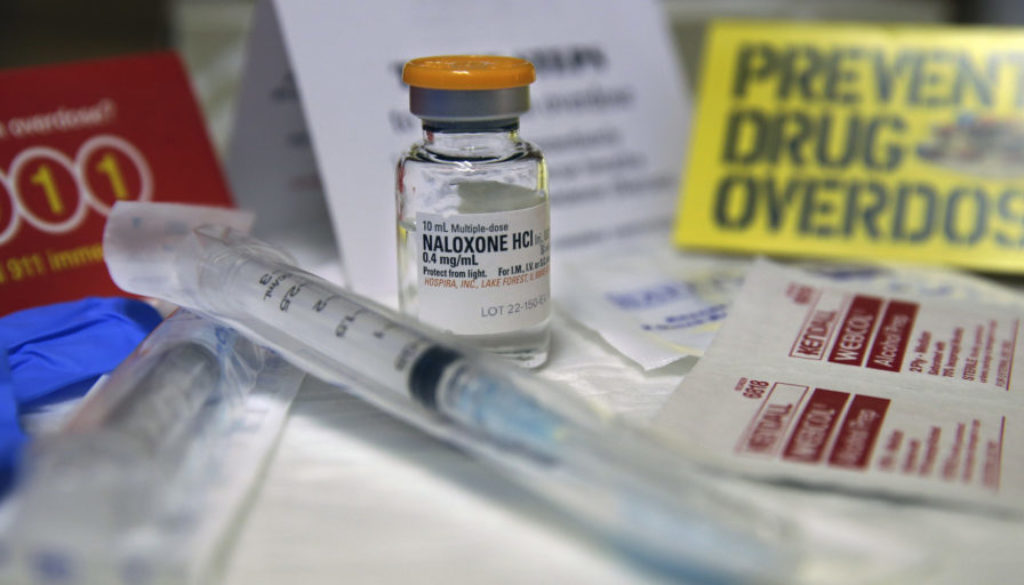

2. You Need to Get a Naloxone Rescue Kit for Yourself and For Your Kid

Naloxone is a medication that reverses opioid overdoses. It has no misuse potential and is currently legal to possess in 43 states. It’s accessible by prescription, through overdose prevention organizations, and over the counter in some states. Most EMTs and many police now carry naloxone and it’s reversed tens of thousands of overdoses.

If your child is using opioids—even as prescribed—get them a naloxone rescue kit. Hang on to one for yourself, too. This doesn’t mean you support what they’re doing. It means you value their life, regardless of what they’re doing.

Don’t get a rescue kit and just tuck it in a drawer. Give your child a kit, teach them how to use it, educate them about overdose prevention, and try to help them avoid feeling the need to use alone (naloxone can’t be self-administered).

3. Methadone and Buprenorphine Are Our Most Effective Tools for Opioid Addiction

Decades of clinical research and consensus statements show medication-assisted treatment (MAT) with methadone or buprenorphine (Suboxone) is the most effective treatment for opioid use disorders. Many parents fall into the trap of trusting the first results that pop up in an online search, which might contain misinformation, and refuse to consider this option.

MAT vastly reduces risks, improves quality of life by almost every measure, and has the highest retention rate of any treatment. Most of the negative claims about it—that it rots your bones, that switching one drug for another doesn’t help, that withdrawal is worse than heroin—are simply myths, with no clinical evidence to support them.

If your child asks for help getting into an MAT program, help them. It won’t solve all their problems immediately, but will greatly increased their chance of staying alive, while creating an environment conducive to making further healthy choices. It took me nine long years to accept this option, and even then, stigma against this treatment set me up for a bumpy ride. Encourage your loved one to stay in MAT for as long as they, and their doctor, deem necessary.

4. Syringe Exchange Improves Health and Can Be a Gateway to Other Positive Changes

You may find this difficult, but when you come across a stash of your child’s syringes, tossing them in the garbage is not the best choice. Instead, you can use it as an opportunity to discuss transmission of diseases like HIV and hepatitis C(HCV).

This isn’t enabling. It’s educating someone who will probably continue using anyway, and equipping them with tools to protect their health. HIV and HCV have devastating, lifelong health effects that can cause more long-term damage than substance use.

It’s also an opportunity to locate a local harm reduction or syringe exchange program (SEP), if you’re lucky enough to have one. Access to harm reduction services doesn’t increase drug use and can serve as stepping stones toward healthier choices. (2) SEPs are also shown to increase the chance your loved one will seek treatment.(3)

5. “Traditional” Treatment Models Carry Significant Risks

The dominant narrative that rehab and 12-step programs are the “go-to” treatment options has crumbled in recent years. Still, many parents pour tens of thousands of dollars into “luxury” rehabs—often taking out second mortgages or draining college funds to pay private facilities, which aren’t subject to government or professional oversight. Many 12-step-based treatment programs cite high success rates, with little or no supporting data (many patients drop out before completing programs). If staying off of drugs entirely is the aim, 12-step programs’ real “success” rate is no higher than 10 percent.

Sober living homes, which can also be extremely expensive, are almost completelyunregulated and rarely offer counseling. They can be operated by anyone, even individuals with no clinical experience, making them ripe for exploitation. This discredits facilities that actually do offer professional care and evidence-based treatment. The problem is, it’s hard to tell the difference.

Drug courts also demonstrate limited success. They rarely permit MAT, frequently cherry-pick cases that artificially inflate success rates, and many don’t accept participants with long histories of heroin use. (4) Studies indicate participants might serve more jail time than if they’d just accepted a sentence up front. (5)

Abstinence-only models can reduce tolerance and result in an overdose in the case of relapse. This isn’t to say these models aren’t right for some people, but giving your child a voice in determining what level of care is right for them, and adjusting it as needed, is critical to long-term success.

6. We Are Not Safer in Jail

I served years in jail because of my heroin use and have heard countless parents with good, but misguided, intentions make statements like: “At least I know where my baby is,” or “at least they’re safe” when they’re in jail.

No. Jail is not safe. It’s the worst place we could be—worse than living on the streets. Our culture is obsessed with trying to solve problems through incarceration, an attitude that’s flooded jails and prisons with nonviolent drug offenders.

We’re often denied medical care during withdrawal, which can lead to serious health conditions, including death. Jails and prisons rarely resemble the sanitized settings of voyeuristic “prison porn” or sensationalized television and films. They’re dangerous, filthy places where incarcerated people are subject to physical and sexual violence from other inmates and corrections officers.

Incarceration can create lasting mental and emotional trauma. Psychiatrists have identified post-incarceration syndrome (PICS), a proposed sub-type of PTSD, as a consequence of incarceration. Symptoms includes increased risk of recidivism and reactive substance use. On top of that, a criminal record robs us of future opportunities for education and employment.

7. It’s Important to Be Aware of the Role Mental Health Can Play

A 2014 SAMHSA report shows almost 40 percent of people with a substance use disorder (SUD) also have a diagnosed mental health disorder. Over two million of this population are diagnosed with serious mental illness (SMI). More than half of adolescent mental health disorders are undiagnosed. That likely extends into adulthood, as it did for me.

I’ve heard parents share stories of children who begged, “Please, try to understand.” It’s difficult for parents to understand when even we don’t understand the symptoms we’re living with. The stigma associated with mental illness, worries about being a social outcast or parasite, and media portrayals of people with SMI converge to prevent us from seeking help.

When I was 16, I first noticed my own symptoms of conditions that wouldn’t be diagnosed until two decades later. Onset of most mental illness begins at an early age. Talking with children about mental health, helping them understand what’s happening in their rapidly-changing brains, and screening for symptoms during adolescence can prevent more serious issues later on. Screenings and brief interventions can interrupt mental health and substance use issues before they become unmanageable.

8. Valuable Resources and Educational Tools Are Available to Families

Helping a child with an SUD shouldn’t come at the cost of caring for yourself. But “detaching with love,” a concept promoted by Al-Anon, won’t reconnect you with your child (often called “the addict”, a depersonalizing term I hope you never use). There are alternatives to Al-Anon, like SMART for Family and Friends, which offers tools and support options to reconnect while still prioritizing self-care.

The Drug Policy Alliance offers resources for parents, which can equip them with skills to talk openly and honestly about drugs before their children start using or once they’ve started experimenting. It’s important for parents to be able to distinguish between substance use and harmful substance use.

Confrontational tactics, like interventions, can isolate and traumatize a child, while coerced treatment is less successful than voluntary treatment. Structured programs, like Community Reinforcement Approach and Family Training (CRAFT), offer healthy, evidence-based alternatives for approaching your child. We’re looking for understanding and we need compassion—not “tough love.”

9. The Most Important Thing You Can Do Is Create the Connections That Lead to Healing

So we return to where we started: Why do people use substances like heroin? There is no one reason. But there are several common factors, some sort of trauma, unmanaged stress and social isolation among them. Unlike mental health disorders, these factors are sometimes easier to address.

Dr. Gabor Maté, a renowned physician and harm reductionist, writes that unconditional love is key to healing the pain that leads to addiction. One woman he worked with explained that her first time using heroin felt like “a warm, soft hug.“

My first time produced a similar sense of comfort—what I would consider “normalcy.” What others take for granted as part of life somehow skipped over me.

Johann Hari, the author and Influence columnist, makes a similar connection, placing social isolation at the center of addiction (there’s evidence to support this).Hari identifies a likely starting point for the healing process: “[T]he opposite of addiction is not sobriety. It is human connection.”

My journey toward healing wouldn’t begin until I made that connection, accepted myself and others unconditionally, and found a sense of community in other parts of my life.

I don’t have all the answers you want, but I hope this is a helpful starting point. Be aware of the good news that, even without treatment, most people with substance use disorders do get better.

Put your wellness first, but remember: Your simple, compassionate connection and willingness to meet your love one where they are in life can set them on the path toward healing.

This article was originally published by The Influence, a news site that covers the full spectrum of human relationships with drugs. Follow The Influence on Facebookor Twitter.

References:

1. Huddleston, West, Doug Marlowe and Rachel Casebolt. Painting the Current Picture: A National Report Card on Drug Courts and Other Problem-Solving Court Programs in the United States, National Drug Court Institute 2(1), 2008

2. Jennifer Murphy, Illness or Deviance? Drug Courts, Drug Treatment, and the Ambiguity of Addiction, 2008

3. Ralph E. Tarter et al, “Predictors of Marijuana Use in Adolescents Before and After Licit Drug Use: Examinations of the Gateway Hypothesis,” The American Journal of Psychiatry 163, no. 12 (2006)

4. Institute of Medicine. Preventing HIV Infection Among Injecting Drug Users in High-Risk Countries. An Assessment of the Evidence. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2006.

5. Hagan H, McGough JP, Thiede H, Hopkins S, Duchin J, Alexander ER., “Reduced injection frequency and increased entry and retention in drug treatment associated with needle-exchange participation in Seattle drug injectors,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, vol. 19, 2000, p. 247-252.

Jeremy Galloway is harm reduction coordinator at Families for Sensible Drug Policy, program director at Southeast Harm Reduction Project, co-founder of Georgia Overdose Prevention, and a state-certified peer recovery specialist. He lives in North Georgia with his wife and three cats. He writes and speaks regionally about drug policy reform, harm reduction, his experiences, and the importance of including the voices of directly impacted people in policy decisions.